Nasal discharges are common in horses, with some indicative of a serious problem and some just nuisance value. They are, however, all worthy of investigation whenever they persist and show no improvement with either time or treatment.

Nasal discharges can be described in several ways: purulent (pussy), serous (watery) or haemorrhagic (bloody), bilateral (both nostrils) or unilateral (one nostril). Nasal discharges are usually bilateral when the discharge arises from the lungs or the pharynx (throat region), and are expelled by running down and out both nasal passages.

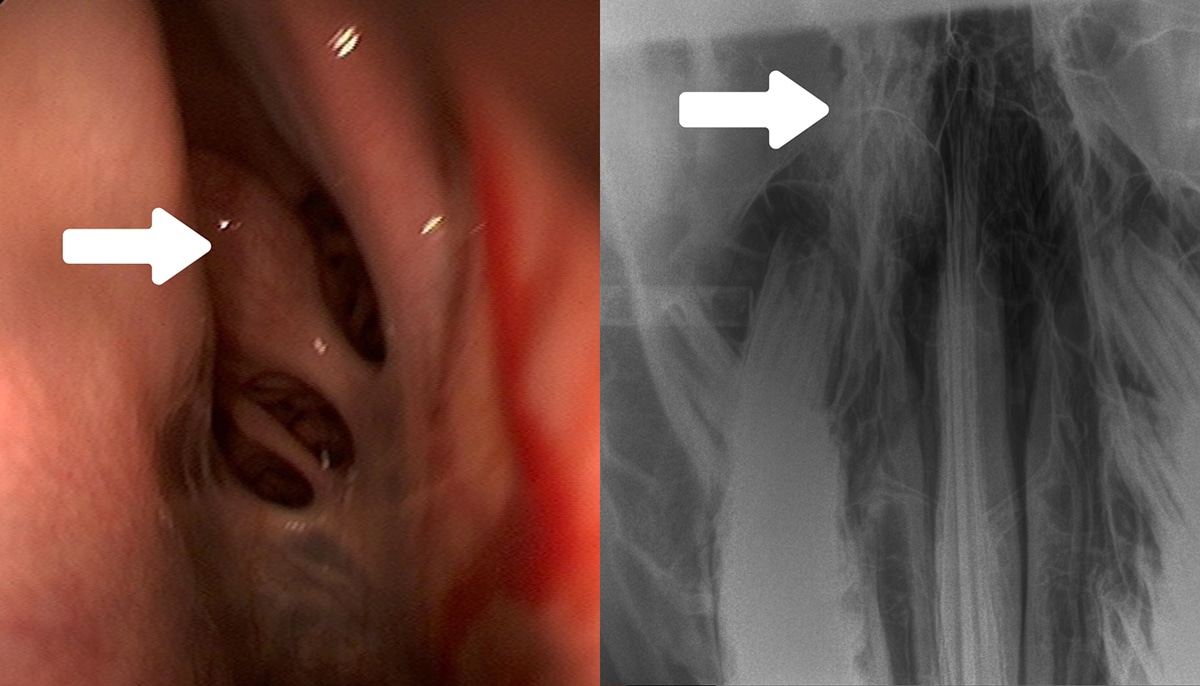

This is a photo of a horse with a mixed nasal discharge (mucopurulent and haemorrhagic). The horse had a secondary infection in the sinus because of the ethmoid haematoma blocking his sinus passage.

When the discharge is only from one nostril, it can often mean the discharge originates from a site forward of the pharynx. Unless there are circumstances that cause the discharge to be drawn into the pharynx and then out, the flow of discharge is down and out the shortest route, meaning that it runs out the nostril on the side it originates.

The exception to this can be when the mucus or blood originates from one of the guttural pouches in the pharynx. As the opening to the guttural pouch is either on the left or the right side of the pharynx, most of the discharge will travel down the one nasal passage, with the occasional small amount seen in the other nostril.

“Ethmoid haematomas are

benign tumours that originate

from within the nasal passages

and paranasal sinuses….”

CASE STUDY

Recently, I was presented with an aged pony that had a mucopurulent nasal discharge from his right nostril. The gelding had recently travelled to Melbourne and there was no known prior history of a nasal discharge. The gelding was otherwise well, bright and eating up, as well as urinating and defaecating without any difficulties. Worming tetanus/strangles and Hendra vaccinations were all up to date.

The owners of the pony believed the nasal discharge was a simple cold from travelling that would resolve within a few days. The horse was rested and given an opportunity for the discharge to resolve; however, after a week, there had been no improvement, and I was asked to investigate the cause.

Haemorrhagic discharge from a progressive ethmoid haematoma (PEH).

The second option was to perform a standing surgery on the pony and remove the mass prior to obtaining a definitive diagnosis. Given the mass was highly suspicious of being a PEH, based on the clinical presentation, it was decided to go straight to surgery and remove it and then confirm the diagnosis after removal.

The pony was referred to an equine hospital for surgery and the mass was removed standing via a large nasal flap and was confirmed to be a progressive ethmoid haematoma.

BENIGN TUMOURS

Ethmoid haematomas are benign tumours that originate from the thin, scrolled bony structures called turbinates (sometimes referred to as ethmoid turbinate) that are located within the nasal passages and paranasal sinuses. The turbinates are covered in mucous membranes and perform a very important role in warming and humidifying the air the horse inhales. The curved nature of a turbinate provides a large surface area of well-vascularised mucosa that can also trap debris and prevent it reaching the lungs. The mucosal lining also detects certain antigens and stimulates the immune system to mount an inflammatory response if required.

The turbinate bones are thin and fragile and when damaged, as occurs with head trauma and the occasional stomach tubing, bleed profusely. The bloody nasal discharge in this pony was caused by the destruction of the affected turbinate. As the PEH grew and expanded into the nasal passages and sinuses, the turbinate and sinus were deformed and then fractured to make room for the mass.

PEH are tumours composed of abnormal blood and lymph vessels and arise from the mucosal tissue of the turbinate or the sinuses (usually the maxillary or the sphenopalatine sinuses). They are not cancerous and do not metastasise to other sites’ however, they continue to grow and expand within the confined space of the nasal passage and sinuses, causing the surrounding structures to be destroyed.

The exact reason behind a PEH developing in the ethmoid turbinate or paranasal sinus is unknown but it has been speculated that a haemorrhage in the tissues beneath the epithelium becomes encapsulated and then continues to grow, but this is unproven.

The characteristic feature usually seen is a haemorrhagic nasal discharge from one nostril, although they can sometimes occur bilaterally and cause a bloody nasal discharge from both nostrils. Other symptoms can include facial distortion, a foul smell from the nostril and a respiratory noise if the mass protrudes into the nasal passages.

With this pony, the mucopurulent discharge initially seen was due to a secondary infection that occurred when the PEH interfered with the normal functioning and drainage of the sinus, allowing bacteria to infect the site and a mucopurulent discharge to form. Bleeding could be seen mixed in with the mucopurulent discharge but was more apparent once the secondary infection was resolved.

These tumours are investigated using one or more of the following diagnostic procedures – endoscopy, CT scans or radiology. In many cases, the PEH can be visualised directly when the scope is passed into the nasal passage and the turbinate is inspected. However, when the PEH originates in the sinus, the lesion cannot be visualised directly unless extensive damage has occurred, and the nasal wall is destroyed.

Haemorrhagic discharge coming from a PEH in the sinus; the ethmoid turbinate was normal in this case (arrow, left image). Many PEHs start on this turbinate and are visible when scoped. The second image (right) is an x-ray of the skull of a horse, with an ethmoid haematoma in the right sinus (arrow). The affected area is much whiter compared to the corresponding side on the left (the right sinus is to the left of the image).

In the case of our pony, no PEH was seen as there was too much swelling in the right nasal passage for the scope to be advanced far enough in and the small area that could be visualised was full of mucopurulent discharge. Using the endoscope was helpful though, as when used via the left nostril it allowed us to rule out any problems with the guttural pouches, the lungs and the left nasal turbinate.

When small and the PEH can be visualised on the turbinate, it has a very characteristic appearance and presents as a yellow/green rounded mass on the turbinate. An X-ray is used to identify any abnormalities within the skull, particularly within the sinus. PEH are generally well encapsulated; they appear as a well-defined oval mass on one side of the skull, which sometimes causes the nasal septum to deviate towards the unaffected side.

If the PEH happens to be bilateral, a mass will be seen on both sides of the skull. Biopsies are seldom used to identify the mass as the PEH can be well encapsulated and require a large, deep biopsy to be taken to confirm the diagnosis, and this then carries a high risk of severe haemorrhage due to the vascular nature of the tumour.

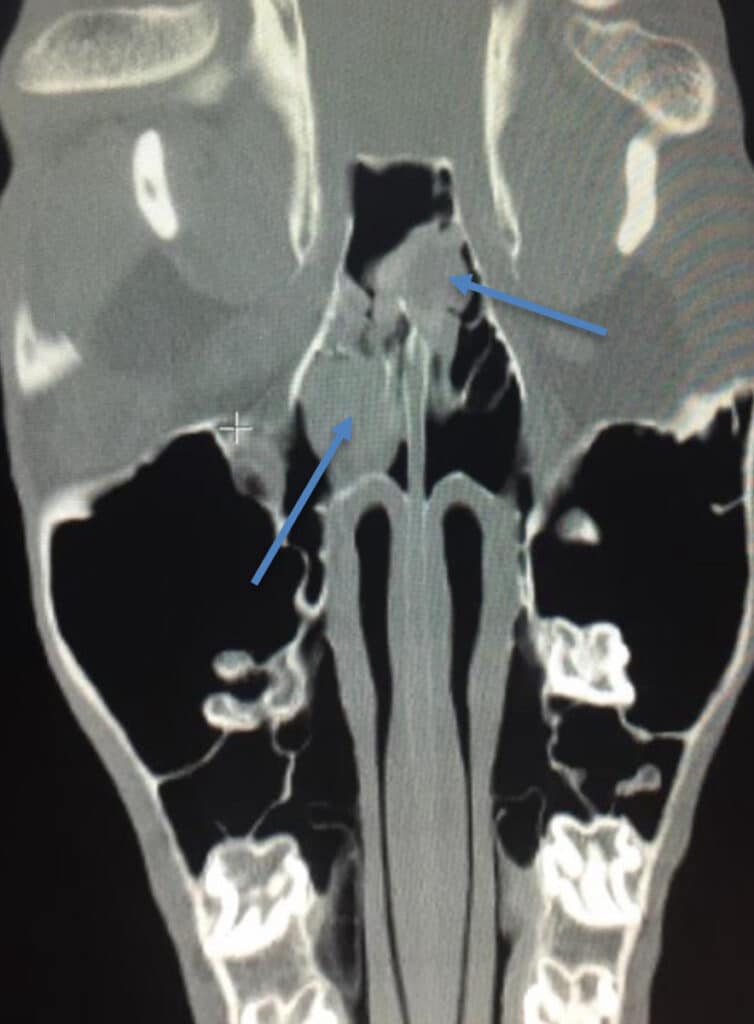

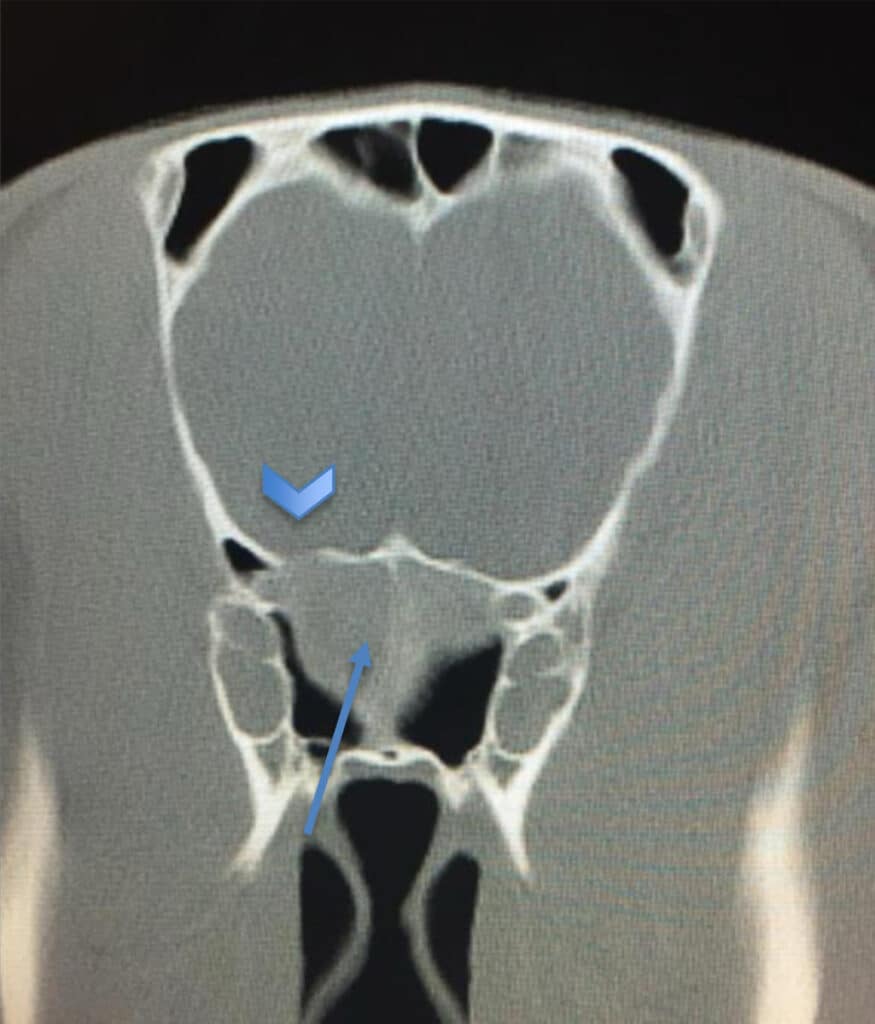

This is a CT image of a horse with two ethmoid haematomas, one in each sinus. An x-ray could not adequately show the two tumours; therefore, a CT was required to get a better image.

“Biopsies are seldom used

to identify the mass…”

SEVERAL FORMS OF TREATMENT

There are several forms of treatment available to remove PEH, but the predominant treatments used are surgical (conventional and laser) and transendoscopic chemical ablation using intralesional injections of formalin into the mass. Other reported treatments include cryotherapy and transendoscopic removal using a snare.

In early times, PEH were removed under general anaesthesia but there was a huge risk of exsanguination or bleeding to death due to the enormous amount of haemorrhaging that could occur. Blood transfusions were often on standby as a precaution before the surgery was attempted, and ample packing of the site was required to try and stem any bleeding.

Nowadays, the surgery is performed on the standing, heavily sedated horse as the risk of haemorrhage is greatly reduced with the horse in the standing position rather than lying down. In this case the pony was sedated and a flap of bone created and lifted to allow access into the sinus and the EH removed. The flap is then replaced and the skin sutured and allowed to heal.

The bone flap generally heals very well but complications can occur with sequestrums, wound breakdown and infection. The important aspect of surgery is to ensure the base of the PEH has been removed or ablated, as failure to remove the entire mass generally results in the tumour regrowing.

The other common form of treatment, known as chemical ablation, is to inject formalin into the lesion every week, causing the mass to shrink until it disappears. This can take many weeks and is usually well tolerated by the horse. The procedure involves scoping the horse and using a specialised instrument that is passed through the biopsy channel of the endoscope and enables the veterinarian to pierce the tumour and inject formalin.

The decision to do either the surgery or the formalin injections is an individual decision determined by discussions between the vet and the owner and often based on previous success or failure that the vet has encountered with the different procedures, and also the availability of the vet and horse should weekly visits be required. It is also realistically limited to a PEH that originates in the ethmoid turbinate and is accessible via the endoscope. A PEH that originates within the sinuses will require surgery as it will not be fully accessible or even visible using an endoscope.

Unfortunately, not all PEH will be amenable to treatment as those that originate in the sinus can sometimes become very large and encroach into the brain cavity before being diagnosed, greatly reducing the treatment options and leaving humane euthanasia as the only option.

This CT image shows the PEH on the left of the image (the right sinus) has progressed and expanded through the cribriform plate and into the area housing the brain (large area). Sadly, this horse required euthanasia as the PEH was inaccessible for surgery.

HIGH RATE OF RECURRENCE

Regardless of the type of treatment, PEH has a high rate of recurrence and when they do recur, it is often within the first 1-2 years after removal. Recurrence rates of the PEH have been cited up to 50% and are likely to occur if the base of the tumour is not removed or ablated fully at the time of the surgery or treatment with formalin is stopped prematurely.

Once removed, the horse should undergo frequent follow-up assessments, normally involving endoscopic examination every 1-2 months in the first few years and six-monthly after this. For tumours that originated within the sinus, X-rays of the skull may be required every three months as the endoscope will not be able to identify the PEH until it is large enough to affect the nasal passages, which is too late.

CT scans would be the preferred method to follow up and identify a recurrence; however, the current cost and ease of availability makes this less accessible to most owners but may be warranted on an annual basis.

A mucopurulent nasal discharge isn’t always just a “snotty nose”, and nor does a bloody nose always mean the horse has knocked its head. Sometimes we need to delve deeper when our horse or pony presents with a nasal discharge, as we found out with this pony. EQ