Age and experience can bring deeper insight into the art of dressage. The sport has evolved and now many of us are training for connection, not competition — finding joy in partnership over podiums.

The most special thing about the sport of dressage is that not only do women and men compete on equal footing, and horses come in all sizes and types — but also, age does not weary riders. Well… physically, age does weary us. But when it comes to training a horse for dressage, weariness can actually become an advantage.

Reaching Grand Prix isn’t about strength alone — it’s about feel, timing, patience, and wisdom. You can’t put an old head on young shoulders.

MY JOURNEY

I’m a Grand Prix rider, judge, coach, committee member and all-round dressage enthusiast. Now 71 years old, I’ve been active in the sport for 55 years.

I began riding at age 13 on school horses, riding along the beach and through the bush in southwest Western Australia. I then purchased a $500 Thoroughbred with bowed tendons. That horse, Bromont, was shortlisted for the Moscow Olympics in eventing.

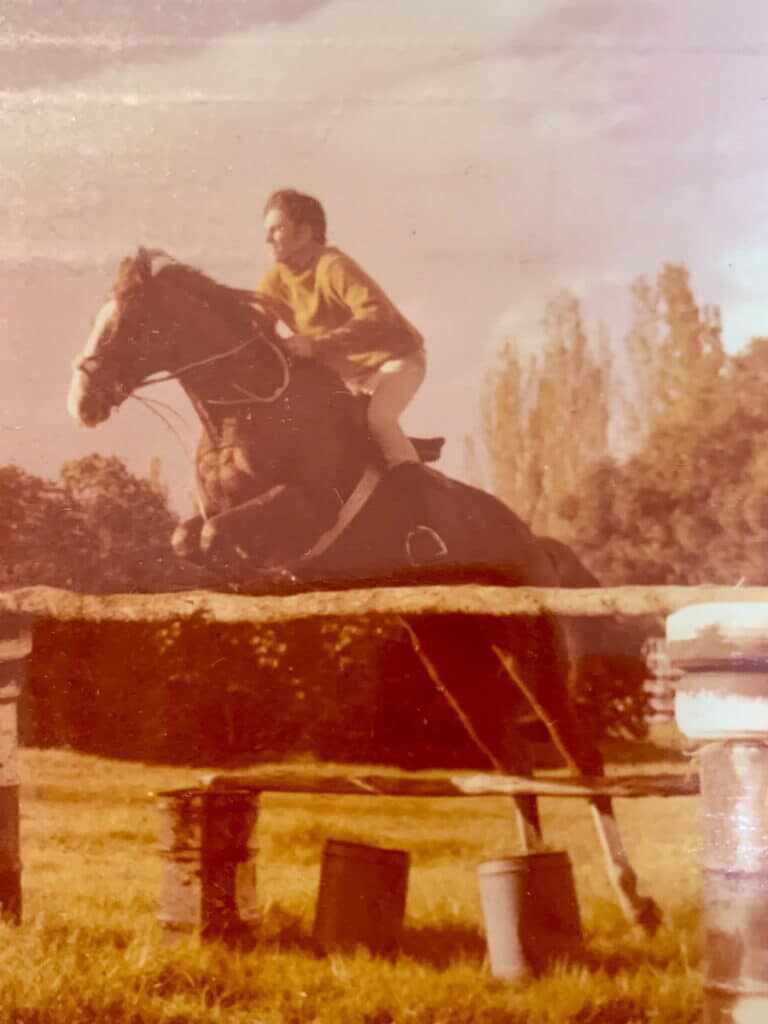

Roger Fitzhardinge jumping his horse, Misere, in the early days of his equestrian career. Needless to say, he would now never ride without a helmet! Image supplied.

As a younger rider, my focus was very much on being successful — and on winning. Success opened doors: it meant greater earning potential, more opportunities to sell horses, and a stronger personal profile. There was constant pressure to ride well, to beat the best at the level my horses were competing. And I know I wasn’t alone in this. For many riders, this is the driving force behind their early years in the sport.

I was never part of the elite echelon of international dressage competitors. I was, and still am, one of many dedicated dressage riders who take competition and training seriously. But now, at 71 — with a spinal fusion, two knee replacements, an artificial joint in my wrist, and the usual collection of age-related aches and pains — my outlook on the sport, particularly in my riding and training, has changed significantly.

I don’t have the physical strength I once did — but I have experience. I no longer train for medals. I train for the connection. For the horse. The joy is no longer in the ribbons, but in the riding and training. When my horse offers a clean change, or goes softly on the bit, that’s our victory. I have goals and feelings I want to achieve for a more harmonious ride and a better-quality understanding between the two of us.

As older riders, many of us don’t bounce like we used to. Our balance has shifted. Our reflexes are slower. But our feel — our sensitivity — is sharper than ever. We can’t muscle horses into frames. We guide them with softness, with quiet perception, with intuition and sensitivity. Modern horses are bred for movement, character and aptitude towards their genetic purpose. That temperament doesn’t mean “quiet” — it means willing. It means a readiness to learn, not overreact. As we age, we choose our horses more carefully. We can’t afford to fall, so the partnership through training and confidence in each other matters more than ever.

I no longer feel the need to compete. I’ve been there. I’ve done that. And to be honest, being under constant scrutiny from judges can wear you down. These days, I ride nearly every day and I still train as if I’m aiming for the top levels of competition. But now, there’s no pressure to climb the levels, no rush to reach Grand Prix. Every day is a stepping stone, a small progression toward an ideal, without the weight of expectation or disappointment when things don’t go quite right.

Without the competitive pressure, I can take the good with the not-so-good, and I make every ride a positive step forward. I believe I have far better empathy with my horse now. I’m far more mindful in the way I ride. No longer can I rely on strength to shape a horse’s frame. Instead, being less physically strong has pushed me to develop softer, more refined approaches to engagement and balance.

Roger is enjoying the training journey with his current horse, Bloomfield Vision. Image supplied.

It’s an interesting and rewarding scenario. I feel incredibly grateful for the wealth of experience I’ve had and for the many people who have helped me along the way. All that knowledge and support now guides how I ride at home, just for myself.

Whether I compete again or not is beside the point. I absolutely love watching the younger, more athletic riders — they look incredible in the saddle. But age, as we know, does have a way of pulling things south!

Still, I can honestly say: I’ve never enjoyed horses, riding, and dressage as much as I do now. It’s a tougher sport to be competitive in now, especially with all the politics and social media feedback from an often harsh vocal minority. However, I still wouldn’t stop or think twice about competing if I so wanted.

CHANGING SPORT

The sport of dressage, from the way horses go in frames and movement, to how they’re trained and judged, has changed dramatically over the last decades. Today’s riders have access to international trainers, imported horses, pristine arena surfaces, and endless streams of video content. The riders who came up before all that — those now in their 60s and 70s — carry a kind of insight that can’t be taught through watching YouTube.

Those early years created horsemen and horsewomen with true feel. We rode bareback on off-the-track Thoroughbreds and fiery Arabians. We’d never seen piaffe in the flesh — only in grainy photos and read about it in educational dressage books that enthusiasts wrote. We imagined what it must feel like. And we tried to recreate it.

Among these Aussie riders are Olympian Mary Hanna; Rozzie Ryan, who represented Australia internationally many times; competitor and stud manager Dirk Dijkstra; and Dr Kerry Mack, an accomplished trainer of multiple Grand Prix horses, who has also bred and trained successful young horses, and rode at World Cup level jumping.

Alongside other seasoned riders, they share strikingly similar reflections on how the sport has evolved — sometimes for the better, sometimes not.

KERRY MACK

“I still love to train, to compete, and to do my best,” says Kerry Mack. “Back in the day, training was raw and exciting. We learned from one another. We watched each other, we listened, and when some of us had the opportunity to compete overseas, we brought that knowledge home. The goal was always to produce a horse to perform the movements required at the next competition.”

Kerry Mack began her riding career aged three with her pony Midge. Image supplied.

Like others, Kerry speak of a new kind of wisdom — training not with force, but with thoughtfulness.

“Our bodies aren’t as supple anymore, and let’s be honest, we don’t bounce like we used to if we fall off! We train smarter now. We think more about the welfare of our horses, the right way to solve training issues, and we do it without the pressure of needing to ‘get it right by the weekend.’”

There’s a joy in that — less pressure, more partnership.

For Kerry, the essence of dressage lies in the training, the relationship, and the artistry of bringing a horse from basics to Grand Prix with patience and love. “It’s the mental connection, the feel, the communication — that’s what dressage is to me. Training a horse for balance, suppleness and obedience, developing his character and his physical prowess. I just love to ride and train.”

Kerry also feels that while it’s crucial to prioritise equine wellbeing in the sport, the welfare card has at times be misused – usually by a vocal minority. “I don’t support overtight nosebands, but nor do I support demonising professional riders who are prepared to take on difficult horses,” she says.

Kerry competing at Equitana with stallion Mayfield Pzazz in 2015. Image by Michelle Terlato.

“In Australia most dressage

horses live in luxury…”

“I work in Alice Springs, where the incarceration in gaol rates are high, and jails are overflowing with indigenous people who suffer terrible poverty, trauma, grief and loss. Inmates don’t have air conditioning in 44°C heat. Children as young as 11 are being incarcerated sometimes for trivial offences; that is a welfare concern,” says Kerry.

“In Australia most dressage horses live in luxury. They are pampered and deeply cared for. My horses are looked after to the highest standard. They’re exercised regularly, turned out in paddocks as much as possible, enjoy up to six feeds a day, and receive any necessary supplements to keep them comfortable and healthy. They are stabled when needed and are warm in winter, cool in summer. They’re not stressed. They love their lives and their work.”

Kerry’s Grand Prix stallion Mayfield Pzazz is a living testament to the benefits of a life in dressage — well-kept, sound, and still full of spirit at 28 years of age.

Many agree that what is currently missing is camaraderie and mutual respect between judges, riders, the national bodies, and the FEI. There’s a prevailing sense that riders must accept whatever judgment is handed down, without question. “We need more openness, more support, and for judges, FEI and national federations to stand with riders — not against them.”

DIRK DIJKSTRA

Dirk Dijkstra is a Grand Prix competitor, coach, A-level judge, dressage selector, and successful breeder whose equestrian career began in 1968 as a 12-year-old in The Netherlands.

“I still ride horses every day, but my approach has shifted significantly,” reflects Dirk. “The pressure to produce high-level horses for competition and sale no longer weighs heavily on me. Instead, I focus on training day by day, enjoying the process without the stress.”

Dirk Dijkstra competing with his now-retired Grand Prix stallion AEA Metallic. Image by Roger Fitzhardinge.

For Dirk, competing still remains a passion – however the dates for competitions have become just notes on the calendar. “They no longer hold the same level of stress for my horses or myself. The sport has transformed considerably since I first started competing. One significant change is the impact of social media, which has become a serious issue. A small group, often with little to no experience in the sport or with horses, can wield significant influence. It’s astonishing to witness, but it also reflects how much our lives and the world around us have changed.”

MARY HANNA

Mary Hanna is a six-time Olympian – and travelling reserve for the recent Paris Olympics – as well as a coach and mentor.

“As the years proceed so does my thirst to continue riding, learning and competing. It’s just something in me and I am motivated every day to get out and ride and train my horses,” says Mary. “They get me out of bed and excited to visit them every day. My values haven’t really changed, as I still train to be the best I can. I love to compete, but also to train to make it as good as I can – and then the competition is secondary.

“I have wonderful horses and of course support that is brilliant. I am not at all as strong as I was, and so I also work hard – especially with my core. If you see me walking around, I look a bit wobbly, but on a horse, I have never felt as secure.

“All the experience I have had helps reduce training mistakes. Trying to undo problems that are trained in is harder than anything, hence nowadays the training is simple with fewer mistakes. The road to Grand Prix is a wonderful one and the road nowadays is a little shorter, simply as experience doesn’t let training mistakes take over. Also, it’s so important to have feel and sensitivity, just as my horses have in return.

“The sport has evolved. Can I say in a good way? Well, it did for many years, and everyone pulled together to lift the standard. Now with the expense, and of course the negative minority on social media, it’s a hard one. I wish there was more transparency with the judges and the riders. It seems a little as if the judges want us to stay quiet and always stick up for them, and I get that, but on the other hand what about the judges sticking up solidly for the riders? I think they sometimes forget this.”

For Mary, there is some sorrow in seeing the sport pulled apart by a vocal minority who, it seems, lack true understanding or lived experience in the discipline. “It’s very sad,” says Mary. “But it will never stop me from loving my horses, riding, and taking each young one through the journey to Grand Prix. That is the heart of dressage — and that is where my heart still lies. I’m still competitive, but now, my competition is with myself.”

Mary competing at the 2014 World Equestrian Games with Sancette.

With no plans of slowing down, Mary draws inspiration from the next generation of riders. “I love helping the younger riders and I love to compete against them as well! It really keeps me on my game. It’s a wonderful sport and I will continue as long as I am upright!”

ROZZIE RYAN

“Aging changes everything,” says Rozzie Ryan. “I’m no longer at my physical peak, but experience now plays a much bigger role in how I ride.” She reflects on how, as a younger rider, she often misread her horse’s reactions. “You think you’re helping, but you can accidentally knock their confidence. Now, I listen more. Horses are always telling you what they can and can’t do — it’s up to us to read them right.”

Like others, Rozzie no longer feels the same pull toward competition. “I loved competing — especially being in the warm-up arena where you learn so much. But things have changed. The sport has become super elite. It used to be that a well-trained horse could be competitive, but now it’s about the million-dollar horses.”

Rozzie reminisces about the early days of international competition: “Our flight to [the inaugural 1990 World Equestrian Games] in Stockholm was wild — Australia, Auckland, Honolulu, Anchorage, Stansted… it was a marathon!”

While air travel as a whole has improved for horses since them, she notes how it has regressed since 9/11, shifting from fast, passenger-combi flights to slower freight-only options. “I’m not sure I’d want to put a horse through that again.”

Despite still owning a talented horse, Rozzie says, “I’ve got no heart for international competition anymore. Judging has become harsh, and social media has had a toxic influence on the sport. Many critics have no idea about the beauty and complexity of the horse-rider relationship.”

Rozzie Ryan in the Grand Prix arena with Jarrah R. Image by Roger Fitzhardinge.

LOOKING AHEAD WITH LOVE

Though some feel disillusioned by the politics, social media negativity and rule changes clouding the sport, their love for dressage — and horses — remains undimmed.

In the end, the wisdom in weary isn’t a burden — it’s a gift. It’s the quiet joy of getting out of bed to ride not for recognition, but for the love of the horse. It’s knowing that the best movements can’t be forced; they arrive naturally, through trust, time, partnership and empathetic, serious training.

Age will not weary the dressage rider! EQ